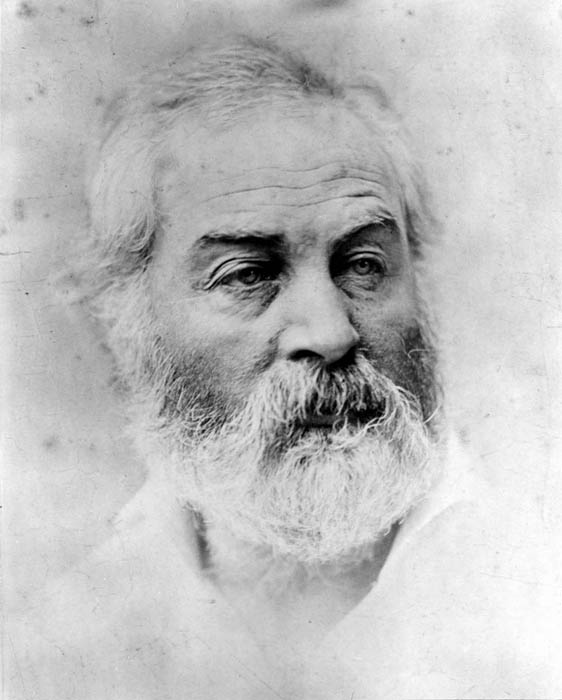

“The Good Grey Poet”, the immortal Walt Whitman, lurker in supermarkets, was born on this day. Our last year’s (2011) birthday-posting has been (surprisingly?) hearteningly, among our most-visited posts (we pray, given his commitment to candor and health, for scholarly pursuit, not for mere prurient interests). That posting included information about the truly remarkable Walt Whitman Archive, whose praises we continue to sing (We “sing the Body Electric“?). That site, we are pleased to report, has been considerably expanded in the past 12 months. Just in the past two months, for example, new Civil War notebooks have been added, along with nearly 450 letters from the Reconstruction years (the complete two-way correspondence from this period will be available in the Fall). The first installment of Whitman’s Civil War journalism is also now on-line and available.

Here on the Allen Ginsberg Project we’ve featured important first-time transcriptions of Allen lecturing on Whitman (in 1975 at Naropa) here. We’ll be publishing more such Ginsberg-on-Whitman in the coming months.

Guess we should also mention “the Gay Succession” once again!

Here’s Allen’s essay from Sulfur (1992) – “Whitman’s Influence: A Mountain Too Vast to Be Seen”:

“Like Poe, Whitman’s breakthru from official conventional nationalist identity to personal self, to subject, subjectivity, to candor of person, sacredness of the unique eccentric curious solitary personal consciousness changed written imaginative conception of the individual around the whole world, and inspired a democratic revolution of mental nature from Leningrad and Paris to Shanghai and Tokyo.

Like Poe, who introduced modern self-consciousness to Baudelaire and Dostoevsky, so Whitman’s exposure of a new self of man and woman empowered every particular soul who heard his long-breathed inspiration. “I celebrate myself, and sing myself/ And what I assume you shall assume…”

This expansive person and expanded verse line affected continental literary consciousness by the turn of the century, Emile Verhaeren in Belgian French, Paul Claudel later with extended strophic verse. The Russian Futurists adapted Whitman’s bold personism – vide Mayakovsky’s “Cloud in Trousers”, Blok‘s “The Twelve”, Khlebnikov‘s vocal experimentation. Perhaps through the French, Japanese and Chinese poets reinvented verse forms and personality of poet – Guo Moruo and Ai Qing [the father of Ai Weiwei – sic] particularly, introduced Whitmanic afflatus and expanded verse line to China by 1919. And Ezra Pound also said “I make a pact with you Walt Whitman” in introducing modernism to American English poetry by World War I – thereby catalyzing renewal of all world poetries. What was Whitman’s effect on Italian Futurists? On Marinetti and Ungaretti?

In Democratic Vistas Whitman warned that unless American materialism were to be enlightened by some spiritual influence, the United States would turn into “the fabled damned of nations”. His spiritual medicine or antidote to poisonous materialism was “adhesiveness“, a generous affection between citizens. In his Preface to “Leaves of Grass“ he prescribed “candor” as the necessary virtue of “poets and orators to come”.

The Good Grey Poet’s own affections and candor led to the excellent tender erotic verse in the “Calamus” section of “Leaves of Grass”, prophesying a gay liberation for American and world literature.

His “Passage to India” predicted a meeting of Eastern and Western thought in our twentieth century, a pragmatic transcendentalism that’s come true with the flavor of meditation practice in American poetry as we approach the second millennium’s end.

His image of universal transitoriness in “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry” has transmitted itself across a century. As the Tibetan lama, the Venerable Chogyam Trungpa, Rinpoche, remarked, Whitman’s writing equals Buddhist sutras in this perception.

“When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d”, his threnody for Lincoln, salutes Death with romantic vigor equal to his salutation to Life, “Salut au Monde”.

And his Sands at Seventy”,[Editorial note – “Sands at Seventy” is actually the title of a sequence of poems in the later Leaves of Grass] “Good-Bye My Fancy”, and “Old Age Echoes” are marvelous short poems of old age, describing with equanimity the “querilities…constipation…whimpering ennui” of body and mind approaching death, signaling farewell, waving goodbye, “garrulous to the very last”. These late lesser known poems are among his most vividly appealing , and prefigure the brief clear-eyed sketches of his poetic grandchildren the Imagist and Objectivist poets William Carlos Williams and Charles Reznikoff. Such poems serve as candid models for my own verse to this day.”

Happy Birthday, Walt!